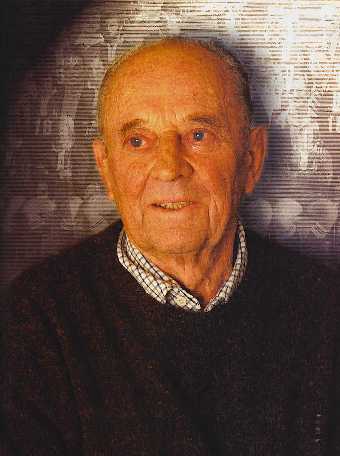

League's little big man

| He remains the

youngest coach in the game's history and is also our

oldest surviving Test captain. Wally O'Connell is one of

rugby league's true living legends BY ANGUS FONTAINE, Rugby League Week 2002 Year Book, pp 12-15. FOR a small man, Wally O'Connell stands mighty tall. As the oldest surviving Kangaroo Test captain and the youngest coach in Australian league history, Wally's stature as a living treasure is assured. But for all his feats on the football field it's the true story behind his legend that is the most amazing. As if standing a diminutive five-foot-three wasn't hindrance enough in the valley of the giants that is frontline football, Wally has only now revealed publicly his most incredible disadvantage - that he played out the entirety of his illustrious career with just over 30 per cent vision in both eyes. |

|

| The story of how O'Connell kept

secret his affliction and went on to become one of the

greats of the game begins back in 1928 when the

five-year-old Wally walked in the back gate of his

eastern suburbs home and caught a kerosene can in the

face, courtesy of his younger brother who was swinging it

about at the time. The blow knocked O'Connell cold and

put him in a coma for five days. When he finally emerged

from the abyss, the vision in his right eye was gone and

the left was "half-shot". But having been

raised on the lore of league by his father, an avid fan

of the game, Wally was never to be diverted from his

destiny. He played on, defying his injury and his size. Not even rheumatic fever at age 14 - a condition which kept him from walking for two whole years - quelled his ambition. Very soon Wally's attacking bursts from five-eighth and his famous ability to mow down the biggest of forwards in boot-strap tackles, catapulted him into first grade for Eastern Suburbs. Although it was O'Connells magic in attack, his uncanny knack for conjuring something out of nothing, switching the play and exploiting the blind-side that was to earn him plaudits across the world, it was the little big man's tackling which rings loudest in the memory of those he came up against. In three seasons Wally never missed a tackle. Then one day at the Sydney Showground, a big forward brushed him off and left him eating dust. So shamed was O'Connell, he deliberately stayed out until midnight to avoid his old man and the belting that was inevitable. "I crept in the window that night quiet as a mouse and switched on the light. There was dad sitting on the bed," recalls Wally today. "He just looked at me with the razor strap in his hand and said 'You missed him', all the while slapping the strap in the palm of his hand. Even though he didn't belt me, I must've been the only bloke in first grade who got one across the backside from his father for missing a tackle!" Yet despite being a frequent nominee as 'player of the round', O'Connell's size kept him out of representative football until 1948. Then Balmain's Ken Stephen withdrew from the NSW side to play New Zealand and Wally - the Waverley Shire whiz-kid - got the call-up he'd craved for so long. He showed no flashes of his customary brilliance in the first half, content just to study his opposition. It wasn't until the second half, with the Kiwis leading comfortably 12-3 that he exploded, sparking his back line into action with a series of exhilarating bursts downfield and turning the tide of the game with guile and sleight of hand. When the final whistle sounded, NSW had triumphed 23-17 and Wally O'Connell had played, in his own words, "a bloody blinder" and was headed for the big time.

He was selected for the Tests against New Zealand that same year and was one of the first selected for the 1948 Kangaroo tour which featured a team of greats like future Kangaroo captains Clive Churchill and Jack Rayner. It was at Headingley on October 9, 1948, that O'Connell reached perhaps the pinnacle of his career. When captain Col Maxwell was ruled out with a leg injury, the selectors turned to the sawn-off spark plug that was Wally to not only coach in the lead-up, but to captain Australia for the first Test played on English soil since the end of World War II. "It was an amazing honour," says Wally, "particularly for a bloke who'd played seven years of first grade without once cracking rep honours. But that whole tour was special because despite there being devastation all over England the people were marvellous. It's what the spirit of sport is all about." Gazing raptly at a photo on the wall of his Bellevue Hill home which captures that historic moment, Wally beams with pride. "You know, on the way back from the toss, a fellow jumped the fence and pressed a silver horseshoe into my palm for luck. I hung it in the dressing-rooms before we ran out and by the time we walked back we'd lost 23-21 but played the most magnificent game you could ever imagine. And not a punch thrown the whole 80 minutes."

But back in Australia, Wally struck

trouble. He had gone for the coaching job at Easts only

to withdraw his nomination when he discovered at the

eleventh hour that the players had signed a letter asking

for Ray Slehr. Instead, he took on a captain-coach

position with Christian Brothers, Wollongong for the 1949

season, where he played out half the season in agony from

kidney stones. True to his contract with Manly, O'Connell sat out the 1950 season thereby forfeiting his Test spot for the Ashes series against Great Britain. At the tender age of 27 years and five days, Wally was made captain and coach of Manly for seasons 1951 and '52. Sadly, this prestigious feat and his restoration in the Test side was not salve enough to heal the wound of missing the Eagles' maiden premiership appearance in '51. Wally had broken his wrist leading his side to an upset 18-8 win over Saints in the final and was left to watch forlornly from the sidelines as Souths crushed his boys in the big one 42-14. It wasn't until 1952 that 'The Evil Eye' caught up with Wally O'Connell. "I'd seen a doctor in 1950 who'd told me that one bad knock to the head and I'd lose my sight for good," says Wally. "but even then I decided to take the risk and play on." And so Wally's secret remained intact right to the very end. "I couldn't tell my family about the risk I was taking because they'd have worried and forbidden me from playing. I couldn't tell my players because they would've protected me too much. I just kept it to myself." When he suffered a 10-inch gash above the eye against Norths at the tail of the 1952 season, Wally knew the game was up. "I caught a boot and it cut me open and that's when I said to myself, 'You've been bloody mad, Wally'. So that was the sign I needed to realise how stupid I'd been. I never walked on the field as a player again." Wally returned to the game to coach the Sea Eagles in 1966-67 and it was during this time that he learned a few tricks young coaches like St George's Nathan Brown might do well to heed. "A coach has got to know the game inside out," says Wally. "He's got to know the strengths of his players, the type of men they are - mentally, physically and emotionally - and how their style of play suits the position they're in. When it all boils down to it, a coach's job is to maximise the potential of every player in his care. Above all, he's got to encourage togetherness as a team and make his players believe in each other." Now a sprightly 79 and fervently toiling away on his own collection of memorabilia whilst penning his long-awaited autobiography, Wally can look back on his years in the game and realise how lucky he was. Although the same eye that caught the flash of a gap or sized up a fast chance on the football field in the '40s and '50s is the same one that has seen him write off no less than 15 cars during the last few decades, rest assured that the eyes of Wally O'Connell are still sparkling. See Also: |